interests

„Cultures get very rigid, and so people who go through extreme states come forward with experiences that balance the rigidity. These states could really enrich cultures, if the culture is open-minded enough to understand that. That’s my great hope.”

Arnold Mindell

In this section, I’m going to describe my areas of interest that are connected to psychotherapy. Probably like in any other discipline, there’s an observable tendency in psychotherapy to wall off against other disciplines – reinforced through different therapy approaches that are seen as conflicting to one another. I believe that this tendency doesn’t benefit the human being which should be in the focus of any psychotherapeutic endeavor – especially in a globalized world in which our human diversity becomes even more visible. Modern psychotherapy needs a willingness to try real openness and integration, culturally, socially and in a dialogue with other scientific disciplines, arts and spirituality. We can impossibly become experts in all those disciplines. For me, it's mainly about keeping my curiosity alive towards the mystery of human existence.

THE EXISTENTIAL

„Nur wer in Angst war, findet Ruhe.“

Søren Kierkegaard

The existential is our shared human experience – it’s those layers in us that we can’t avoid in the end, even if we are trying very hard. It’s the fundamental in us, the rough, the miraculous, the very thing that can’t be therapeutically “cured” but which still leads us in our lives, motivates us, creates ambivalence as well as pain, joy and despair.

Existential issues are for example love, death, war, peace, freedom, responsibility and fear. The philosophical movement of existentialism speaks of being thrown into this world in which humans have to recreate themselves continuously, being “sentenced to freedom”. Life lived encompasses the possibility of failure. And life means constant choice – even if we try not to be conscious of it, we are responsible for ourselves and our lives – throughout all the ambivalence that might be reflected in our choices. Hence the path to selfhood inflicts us with anxiety - the realiziaton of freedom demands to position ourselves as individuals. Facing love and death, we get in touch with deeper levels of our existence, the transcendental and the unbounded, which are the same thing in the end.

There are forms of fear, loneliness, helplessness, ambivalence etc. which can’t be “cured” through psychotherapy. But if we succeed in opening up to those parts of our experience or moreover, accepting our struggle with it, it will make us more human, and thus more whole.

kultur und gesellschaft

„The real hopeless victims of mental illness are to be found among those who appear to be most normal. Many of them are normal because they are so well adjusted to our mode of existence, because their human voice has been silenced so early in their lives, that they do not even struggle or suffer or develop symptoms as the neurotic does. They are normal not in what may be called the absolute sense of the word; they are normal only in relation to a profoundly abnormal society.”

Aldous Huxley

„ ‚Die Souveränität des Volkes wird oftmals nur insofern zum Ausdruck gebracht, als diese einen Staat mit Territorium beansprucht und nationale Identität und Volksgemeinschaft als zwei übereinstimmende Dinge erfindet.‘ (Engin Isin) Ein derartiges Paradigma, das von Natur aus auf Exklusion basiert, bringt, was vielleicht noch gefährlicher ist, neben realen und konkreten Mauern metaphorische und symbolische Mauern hervor, die von Vorstellungen von Andersartigkeit befördert werden, die wiederum durch eine Politik der Angst und Belohnung befeuert werden. Es ist die ‚Mauer in den Köpfen‘, eine deutsche Redensart, die sich besonders schwer niederreißen lässt.“

Sam Bardaouil & Till Fellrath

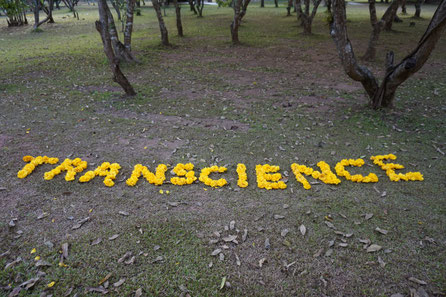

The psychodynamic approach focuses on how people get shaped by their family of origin. There is no doubt that it influences us the most. However, the societal environment in which we grow up forms us as well. Norms, atmospheres, lifestyles etc. differ tremendously – not only between countries or cultures but also between parts and subcultures of “one nationality” – such as growing up on one side or the other in formerly divided Germany. Not only the microcosm but also the macrocosm in which we are raised and that we move through today has a crucial influence on us. Different countries own different souls and different wounds. Historically dramatic incidents – wars, dictatorships etc. – leave the population with trauma that usually keeps being transmitted from one generation to another over a long period of time. Social injustice – social processes of marginalization and exclusion of certain subgroups which might start off with global issues such as being a woman in a patriarchal society – also leaves its traces in the psyche of the individual. It is especially division and splitting, the visible and invisible walls that exist around and go through nationalities, genders, subgroups and even individuals, that are as much painful as they once were supposed to protect us. The holographic approach by Arnold Mindell claims that identical relational structures are mirrored on each level of a system – on the level of the individual, the dyad, the group and the collective. We can’t withdraw from this innate force, but through active engagement with our psyche we can bring forward new impulses even to other levels of the system.

To me, the transcultural perspective in psychotherapy is about acknowledging cultural wounds as well as accepting and integrating differentness. It’s about becoming more conscious of how society has formed us, especially in those ways that contradict the movements of our Selfs (our inner cores). In the end, psychotherapy is nothing but a product of our culture as well. If psychotherapy is to serve humans – especially humans with broad differences – it is necessary to thoroughly look at culturally transmitted norms and values that play out in psychotherapy. If we want to develop as a society, we have to learn from those who stand at its edges. Psychotherapy shouldn’t be a tool of society. It should rather serve society in the sense that it helps to deconstruct beliefs and patterns that restrict spaces for living – in order to create more space for everyone. As cultural norms, beliefs and judgments are deeply tied to our psyche and our habits, this proofs to be a challenging task. Engaging with the foreign helps to become more conscious of those norms – it creates distance to one’s own culture. We may get to know ourselves better by travelling, opening up to people from different cultures or plunging into unfamiliar atmospheres. That is what I appreciate personally as well as professionally.

trauma

„I have come to the conclusion that human beings are born with an innate capacity to triumph over trauma. I believe not only that trauma is curable, but that the healing process can be a catalyst for profound awakening – a portal opening to emotional and genuine spiritual transformation. I have little doubt that as individuals, families, communities, and even nations, we have the capacity to learn how to heal and prevent much of the damage done by trauma. In so doing, we will significantly increase our ability to achieve both our individual and collective dreams.”

Peter Levine

Trauma plays a crucial role in the development of psychological problems which is not be underestimated. Trauma doesn't equal inner conflict or a lack of abilities that can still be developed. It is a wounding of the soul for which there always are factual reasons – threatening, dangerous or hurtful experience. Massive stress that has been caused by that kind of situations becomes engraved into our organisms – even if the actual situation has long ceased. Our perceptions of the present can be distorted by unprocessed trauma to the extent that we constantly feel threatened, endangered and anxious. Simultaneously, some part inside of us shuts down in order to protect us from the unbearability of this experience which we project onto “the world”. Trauma leads to separation and isolation, we lose touch with ourselves and other people. Levine describes trauma as a loss of connection. Our life energy is blocked, life becomes draining and hard. We survive, we do not live. Those are adaptations to the trauma. As we start believing that we ourselves are those adaptations, i.e. we identify with them, we lose contact to our cores.

I don’t conceptualize trauma as merely resulting from experience of obvious violence, abuse and catastrophes. Very often it can be the seemingly small hurts that we are continuously exposed to which leave us with considerable injuries. Trauma does always play a role in extreme suffering such as in “psychiatric disorders”. On the other hand, it can also be well compensated so that we’re not conscious of our wounds. As children we enter this world with a sense of what is good for us and what harms us. If this is fundamentally disrespected by our environment, it is going to result in wounding of the soul. The more we adapt to the very environment that harms us, the less we are going to feel our injuries – however, they will nevertheless have an effect on us and prevent us from thriving. Often, we will pass on our wounds to others by treating them in the same ways as we have once been treated. However, some injuries have shaken us to an extent that makes them hard to be compensated for so that they keep coming up to the surface. Sometimes a mixture of both scenarios will be present.

In therapy it is beneficial to acknowledge our wounds. It will be easier to take this step if we are with someone who sees them and is able to bear the emotions that go along with being shaken deep down, who treats those wounds with care and respect, who doesn't cross the other’s boundaries and shows openness and compassion simultaneously. Traumatized parts have important messages for us to tell. They want to express themselves but they’re gonna need time to gain trust. In that way, each process follows its own timing. I believe that first of all, our profound wounds don’t want to be “treated” – they want to be seen and heard.

Sometimes our wounds are inaccessible not only because we’ve suppressed them but also because they have their roots very early in our lives. The first year of a human’s life is especially influential. In comparison to probably any other kind of mammals, it takes a whole lot longer for human babies to gain independence, for example by being able to walk or simply moving away. At the very beginning, we are defenselessly exposed to our attachment figures as well as to our emotions which we have but can’t process – wounds may be engraved especially deeply. In the prenatal state, we are already sensing, living beings – traumatic influence is possible to take place at that time, too. The more injuries are coming on top, the heavier our earliest injuries will affect us (including the pre-, peri- and postnatal level). Even though never consciously accessible, the process of any human’s own birth is likely to be the most existentially radical incident in their lives, which is accompanied by actual pain and massive threat. If we feel welcome and held in the world we enter into, we develop an effective protection against that kind of experience which in itself can’t be processed. A traumatic childhood can have the consequence that this protection isn’t going to be fully developed, though. Stanislav Grof conceptualized four perinatal matrices that are part of any human birth process. He also described how traumatizing experience later in life could selectively enhance the experience of a certain birth stage in hindsight so that it shapes our perception of the present. In that, he sees a considerable unconscious reason for the human potential for wars and massive violence. Trauma that happened early in life cannot always be proofed by facts but it can be sensed atmospherically, be accessed symbolically and thus be processed.

Additionally, trauma has transgenerational effects. We take on the wounds of our parents, grandparents and so on. Especially for massive trauma, for example war experience, only future generations iwill often be capable of dealing with the issue. Trauma asks for taking on one’s responsibility even though of course we are not responsible for having been hurt in the first place. Recovery, individually as well as collectively, starts with the decision to turn towards those wounds and accept them as ours even though a difficult path might lie ahead of us.